Tariffs as a Class Offensive

Properly contextualized, the tariffs' bumbling rollout is another embarrassing episode in the disintegration of the U.S.-led global economy. But their role in this saga goes mostly unremarked in current debates around trade.

By Jamie Merchant1

As part of his flailing trade wars, Donny Deals has

proposed

100% tariffs on movies made overseas. "The Movie Industry

in America is DYING a very fast death," the president exclaimed,

pointing to the tax breaks offered to shoot overseas as "a

National Security Threat." Placing foreign movie makers in the same camp

as the government's official military enemies might seem

like classic Trumpian hyperbole. But as is often the case, the

president's social media noises are a window to a darker

reality.

Since Trump's first term and continuing into the Biden years, the U.S.

government has gradually redefined trade as a matter of national

security. This is a far cry from yesteryear's tale of

globalization. In that happy fable, trade was the outworking of a

competitive world market bound to link the globe in commercial harmony.

Reducing trade barriers and opening up national markets to the free flow

of capital would attract foreign investment, creating jobs and rising

incomes in the developing world. In turn, the multinational firms of the

rich nations would profit from these investments, expand themselves, and

continue to explore the technological frontier. Everyone wins in a

beneficent order led by its virtuous steward, the United States, avatar

of capitalist freedom.

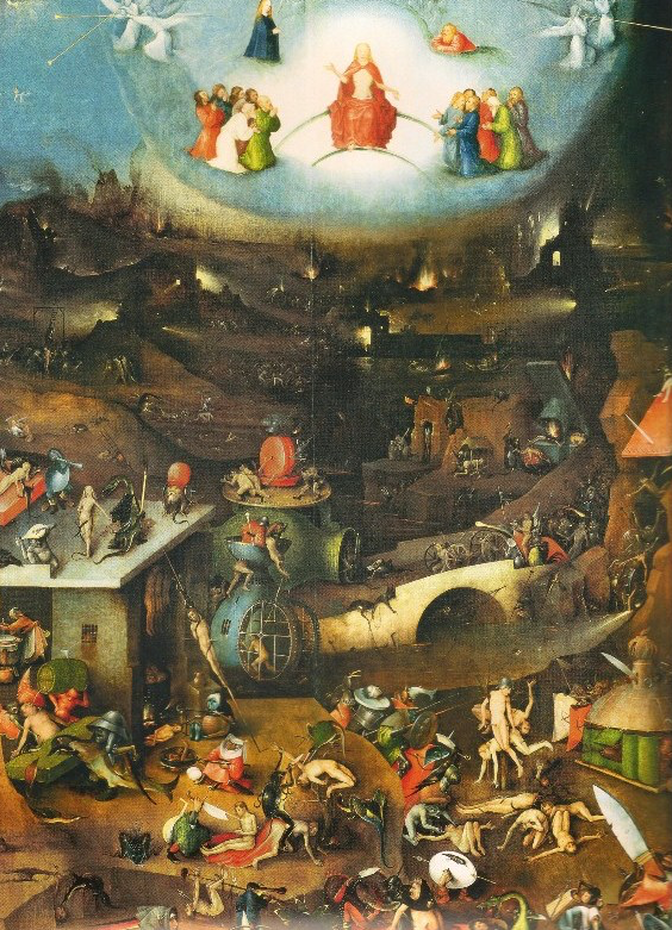

So much for all that. In Trump's gothic rhetoric, trade is

a scene of death and dying, a Darwinian struggle for survival. In this

story, national growth happens not in cooperation with other nations,

but only at their expense. This is not a sharp break with precedent. His

predecessor, Joe Biden, shared the same worldview. So-called

"Bidenomics" doubled down on precedents from

Trump's first term, not only keeping Trump's

tariff regime against China but

escalating

it. The centerpiece of Biden's economic agenda was historic

legislation designed to capture manufacturing investment from its

supposed allies in

Europe

and East

Asia.

Biden's government threatened to penalize foreign producers

if they

traded

with its official enemies in industries deemed critical for

America's national security. Like the Republicans, the

Democrats pursue trade by extortion. Trump II is a more rhetorically

colorful version of the same berserker nationalism that has overtaken

economic statecraft in the U.S. and dominates world politics today.

Properly contextualized, the tariffs' bumbling rollout is another

embarrassing episode in the disintegration of the U.S.-led global

economy. But their role in this saga goes mostly unremarked in current

debates around trade. Instead, mainstream commentary talks about tariff

policy on the terms established by the Trump administration. They are

evaluated as a more or less effective method for achieving its official,

public

goals.

These typically include some mix of reindustrialization and debt

reduction to be achieved by shifting demand for foreign products to home

producers.

The story goes something like this: a reinvigorated manufacturing base

will put U.S. industry on newly competitive footing, reducing the trade

deficit in the balance of payments. The U.S. will no longer need to

borrow so much, allowing a drawdown in government debt. Tariff revenue

will replace taxes, unshackling American business to unleash a new wave

of prosperity. Perhaps they will support U.S. military preparedness by

relocating critical industries inside the country, appeasing a paranoiac

defense establishment.

Can the administration pull it off? Is it economically feasible? Perhaps

a comprehensive

Mar-a-Lago

accord is waiting to be unveiled, revealing Trump's master

plan to the world.

To some, it all seems so chaotic, so unplanned and incompetent that the

idea of a rational basis for it beggars the imagination. Others have

warned against the risk of

"sane-washing"

Trump's agenda by imposing some grand strategy on what

might be nothing more than a historic grift. Of course

Trump's entourage is taking every chance they can to

plunder

wherever and whatever they can, even

fleecing

their own, contemptuous supporters. But to see nothing but kleptocracy

would be an overcorrection, missing the political effects of

Trumponomics beneath the official policy debates.

Tariffs are in part Trump's unique lizard-brained

obsession, an idée fixe of the reality TV real estate tycoon since the

1980s. But their broader historical meaning lies in the context of a

gradual collapse in capital investment and profitability that pushes

national governments to adopt ever more extreme measures in order to

continue appropriating their aliquot parts of a stagnating global pool.

This shows up in virtually every major empirical indicator. GDP growth

rates

across the capitalist world have drifted downward for decades, including

in its supposedly most dynamic new centers, like China.

Labor

productivity and productivity gains from

technology — measured

by what economists call "total factor

productivity"2 — have both steadily decayed as productive investment

has dried up. Such investments are decreasingly profitable for the

world's capitalists, so nation states must bribe them to

invest by throwing trillions in state money at them in the form of tax

breaks, subsidies, grants, and federal contracts. This was the point of

yesterday's enthusiasm for the celebrated return to

industrial policy in the Biden years, now but a distant memory.

Corporations, in turn, increasingly depend on cheap

credit

to finance their activities or even just to continue existing. This is

the case with the symptomatic zombie firms, unprofitable concerns that

survive on easy credit and make up somewhere around

20%

of U.S. public companies. Consequently, the declining profitability of

capital shows up most dramatically in a permanent explosion of

government and private debt. These trends afflict not only the rich

countries, but also the middle- and low-income nations of the Global

South in which development has all but stalled out, most strikingly seen

in the phenomenon of premature

deindustrialization.

What is causing this breakdown? Consider the question of profits. Trump

thinks profits come from deals. Economists think profits would be

competed away in a fair market. Neither understands their source and

function in the broader capitalist economy as a class-based order, in

which a dominant class extracts their wealth from a coerced, toiling

majority. In this society, profits come from the protean fire of human

drives and creativity: labor-power.

If labor-power is the ultimate source of profits, then the drive to ever

higher productivity that defines the capitalist mode of production is

also its undoing. As that source is progressively displaced by more

advanced, capital-intensive production, the total amount of profits

available system-wide to reinvest and expand diminishes. The planetary

ossification of industry overwhelms the capacity of world markets to

absorb its output, intensifying the pressure of competition. Eventually

the process of accumulation reaches a limit in which the profit it is

able to produce isn't enough to further expand accumulation

on a greater scale. This, a general crisis of overaccumulation,

underlies the shattering of world capitalism today.

Global breakdown in capitalist growth is immensely destructive to

societies because it condemns them to a distributional struggle over

shrinking resources. Capitalism is based on the class opposition between

capitalists and the workers they exploit. If productivity is growing,

profits can be shared with the working population in the form of higher

real wages and salaries. But if it slows or stops, the economic surplus

goes to that class with the power to decide who gets what. Oligarchs get

richer as inequality grows more savage by the year. Institutions break

as the frail bonds that hold society together come apart. The fuse is

lit.

The elites are well aware of this. Popular rage at permanently failing

government institutions constantly threatens to boil over. The climate

crisis threatens the basis of human civilization itself. Planetary

upheaval looms. For a capitalist class whose most repulsive members now

simply run the U.S. state directly, the most prudent course is the

empowerment of domestic security and surveillance forces through an

equally empowered, unconstrained executive. Erratic tariff policies that

are unpopular even with many capitalists themselves are just part of the

deal, as Trump would probably say. In the short-term they may be

inconvenient; in the longer term, they are part of a fortification of

class power through a newly emboldened crackdown state. They may even

coerce some favorable concessions from rivals, allowing uncompetitive

industries to limp along a bit longer. In this sense they are indeed a

policy of national security.

If interstate economic conflict was notably absent in the days of

globalization, it was because the elites of all nations were getting

rich plundering their national working classes. Now, the fact that they

turn on each other like ravenous dogs is a harbinger of

capitalism's autumn, a sure sign that growth — like the

mental faculties of our rulers — is expiring.

Seen in this light, the tariffs are neither a more or less rational

policy choice, nor solely an elaborate grift. They are part of a

two-front, worldwide class war unfolding between national bourgeoisies,

on the one hand, and between them and the proletarians of their

respective countries on the other. That is, the tariffs are a recipe for

a renewed ruling class offensive on the workers of the world against a

backdrop of accelerating global decline. They express the economic

breakdown of capitalist society in political form.

"Jamie Merchant lives in Chicago and writes about political theory and radical politics. His book Endgame: Economic Nationalism and Global Decline" was published in the Field Notes series by Reaktion Books. He can be found on Bluesky @jamiemerchant.bsky.social"

First defined by the economist Robert Solow in the 1950s, total factor productivity refers to growth in output when capital and labor investment remain constant, which is usually taken to mean technological innovation.